Killer Triggers Read online

Page 3

I could hear him thundering down the hall and looked up to see Fonto flying toward my door. He made the ninety-degree turn—barely—but then went sliding and crashing into my file cabinet, knocking over the coffeemaker and a full pot on top of it. The broken glass and coffee sprayed across the room.

I jumped up to find Fonto staring at me while chomping on a treat. His look said, “Sorry, Lieutenant Kenda, I just couldn’t help myself.”

I forgave the dog immediately, but his handler had to buy me a new coffeepot.

We used our canines for a wide range of duties. They would help us search for suspects; find illegal drugs and weapons; hunt for cadavers; sniff out explosives; and intimidate, chase down, and subdue bad guys.

As most K-9 trainers will tell you, the dog’s primary responsibility is to protect its handler and fellow officers, as well as the general public. They were formidable weapons when unleashed. They were not pets. We were never supposed to become too attached to our canines. In fact, if a K-9 handler became overly protective of his dog partner, he could be removed from the unit.

Our K-9 units were a critical tool in many of our investigations, and as one case in this book notes, they sometimes were the first to find the killer we were tracking, or the corpse or murder weapon we knew was out there.

For example, I had a case in which a woman heard some scratching at the front door of her home and found her live-in boyfriend sprawled on the porch, covered in blood from a gaping chest wound. He was alive, but he’d been severely stabbed.

When we asked where he’d been, she said, “He was playing poker with some friends in the neighborhood, but I don’t know where they live.”

Apparently, they played high-stakes poker. The game had turned ugly, and our victim got staked. We figured the boyfriend had crawled home before cashing in his chips, so to speak.

They shared a home in the middle of the city. We didn’t know where he’d been, but we knew who could help us figure that out.

We called in the K-9 unit.

The handler arrived and put the dog on the scent. He took off down the street as if he knew where he was going. We followed man’s best friend and tracker two blocks down and one block over. The dog then went up to the porch steps of a home and sat down, looking at us as if to say, “Well, I did my part. You boys take it from here!”

And we did. The dog had led us to the original scene of the assault, and that helped us identify the attacker and charge him. The stabber claimed self-defense, and the grand jury agreed with him.

the bark is bad, but the bite is worse.

Each K-9 handler keeps his dog in the specially designed patrol car. If the officer gets out to make a traffic stop, he still has the power to release the dog remotely thanks to a control box worn on the uniform. If someone gives the officer a hard time, he or she can push a button that opens the door. The dog knows that this isn’t a happy coincidence.

It comes to the officer’s aid in a heartbeat. These are alpha dogs and extremely confrontational if need be. If you ever look at a police dog and it drops its head while maintaining eye contact, know that you have been put on notice. The dog is saying, “You wanna fuck with me or my handler, pal? Check out these teeth!”

The handler is required to give a warning before unleashing the K-9 weapon. If the dog is in its patrol car, the handler will issue the warning over the speakers mounted on the signal bar atop the roof. Those speakers are powerful and loud, so you can’t ignore them. And you shouldn’t!

Say, for example, a suspect is barricaded in a house. The K-9 handler will issue a warning like this: “Come out unarmed, with your hands visible. If you don’t, we will release a police canine and enter the premises forcibly. Injury may result.”

Now, the highly trained dog knows that this warning means “Game on.” It is not an accident, then, that as the warning is being delivered, the dog goes absolutely bat-shit crazy, barking and growling in a roar that the speakers pick up and broadcast to the suspect.

This uproar makes the hound of the Baskervilles sound like Snoopy. The message is that this massive, muscular attack dog is ready and willing to tear into the flesh of the suspect unless compliance is forthcoming. In most cases, that message brings the desired result.

Another helpful hint about police dogs is that they are trained to respond to special commands delivered only in German, so yelling at them won’t work. They won’t listen to you. So you should comply before the dog is released.

The standard response is, “Okay, I’m coming out! Don’t unleash that damned dog!”

This is because all humans share two instinctive fears embedded in our DNA. One is fire. The other is being devoured by a vicious beast. You can see these instincts kick in whenever you walk into a mob of people raising hell and then announce that you will be releasing your police dog unless they disperse peacefully.

One snarl from the canine usually does the trick. You can break up a mob of four hundred people in a couple of minutes. This also works well with suspects who are threatening to shoot us. We had a guy who didn’t get the hint from the 150-pound German shepherd frothing at the mouth. He refused to drop his gun and surrender.

Instead, he turned and ran. The handler released his dog, and it was like a furred torpedo homing in on the target. Then he made the mistake of shooting at the dog. He missed. The dog did not.

They are trained to take away the weapon first. The canine slashed open the suspect’s arm from elbow to wrist, forcing him to drop his gun. Then the dog went to work on the rest of him, sinking its teeth into his thigh. The shepherd’s bite was so powerful that it crushed the guy’s femur, the largest bone in the body.

After we subdued and arrested the screaming suspect, we took him to the emergency room. Doctors feared they might have to amputate his shattered leg, but instead they put a rod in it. The guy limped for the rest of his days, but it could have been worse. I’m certain he never ran from a police dog again, even if it were possible.

If you are contemplating resisting arrest in the future, please keep in mind that a K-9 handler generally can call off his unleashed beast if it is more than twenty feet from a suspect, but if the dog gets any closer, it is an uncontrollable, explosive, and potentially lethal weapon.

A trained attack dog can cause enormous harm and permanent injury, even death, in a matter of seconds. It will tear you limb from limb. We liked to say, “Every badass is a badass until a police canine tears into him. Then they squeal like little girls, screaming for help.”

Bad persons with male parts might want to make a note to self: They will tear off your gonads and eat them. They might be less vicious with females, but I can’t guarantee that.

As a detective, I used K-9 partners mostly for tracking and finding suspects, weapons, and victims. We once had a shooter at a city park who killed a woman and fled. Our police dog tracked the scent for a mile and a quarter, then stopped at a trash can and sat down. We opened it and found the shooter’s clothing, which eventually led us to the killer.

K-9 units are remarkable. To help out a buddy, I actually had one live with me for six months. My friend had been a K-9 patrol officer and handler. He and his dog retired together, which is common. My buddy had to move into an apartment temporarily because he was building a new house and had sold his old one.

Most apartments will not take large German shepherds, even if they’ve retired from the police department. So I invited the dog, Harry Von Stroheim, to live with us. But only after my wife, Kathy, met with Harry and had a heart-to-heart about who really ran things.

Harry was intimidated, which proved once again how smart he was. So Harry moved in for six months. Now, at the time, we had a dog of our own, a chow chow named Simba. Despite the breed’s silly name and fluffy, puffy, lionlike appearance, chows are very strong, quite protective, and can be aggressive.

Fortunately, Harry and Simba str

uck a truce early on. From the first day, they retired to opposite corners and rarely crossed paths. In truth, neither wanted to cross Kathy.

Harry lived with us back in the times when door-to-door salesmen were still common. Most of them were burglars casing out homes. A few of them actually sold magazines or spoiled meat products. Harry’s handler told us that when a stranger came to the door, we should take the dog with us.

“If you get nervous about the person at the door, just reach down and pull up Harry’s collar a half-inch or so. At that command, Harry will go into his bloodthirsty-werewolf routine, and your visitor will make a hasty departure.”

Yes, we tried it. And yes, it worked.

Simba and Harry became a watchdog team. The shepherd watched the front door; the chow watched the back. We had no uninvited visitors drop by either entrance.

We did have one scary incident, though, when a team of carpet installers failed to heed our instructions and warnings about our canine corps. We put Harry and Simba in the kitchen, and Kathy had told the morons not to open any doors there while the workers were installing the new carpet.

“The dogs are aggressive, and we can’t guarantee your safety if you open that door,” my wife told them.

Well, they worked a while and got sweaty, so they opened the patio door, obviously forgetting about the dogs. Both Harry and Simba went out into the yard, scaring the shit out of the workers, who managed to flee. Simba stayed in the cul-de-sac in front of our house, but Harry decided to take a neighborhood tour.

When Kathy came home, Simba rose to greet her. She raised hell with the workers and asked where Harry had gone. They didn’t know.

Kathy went looking for Harry. During her search, she flagged down a passing squad car, introduced herself as my wife, and commandeered it.

“You’ve got to help me find Harry,” she said.

“Who’s Harry?” they asked.

“One of your retired police dogs,” she explained.

“Oh, shit,” they both replied.

If a K-9-unit dog sees a police car, it will go to the car and climb into the back seat, so the patrol officers joined the search. They went one way; Kathy went the other.

She found Harry in a city park full of children. The mighty German shepherd was playing football with a bunch of little kids. The kids were chasing Harry and jumping on him, and he was loving it.

The unsuspecting parents were laughing and hugging the dog, too.

When Harry saw Kathy, his ears went down and his tail dropped between his legs.

“He’s such a great dog,” said one of the parents.

“Yes, he is, but Harry is a former police dog and he is AWOL, so I’m taking him home,” said my wife.

The kids were not in danger, but if some adult had raised a hand to one of them or to Harry, carnage might have ensued.

Harry was a wonderful, smart dog. He responded to twenty-seven verbal commands and hand signals. He had assisted in more than fifty arrests in his long career. Kathy and I loved him, and when it came time for Harry to return to his handler, she tried to keep the dog and send me instead.

The handler was no dummy. He took Harry.

“Harry, let’s go get some bad guys!”

The dog never looked back.

I told you Harry was smart.

Chapter Two:

The Serial Killer Next Door

the trigger: sexual rage

When my daughter, Kris, turned fifteen in 1986, she could shoot the eyes out of rattlesnake at fifty paces. A few years later, she scored 100 percent in her military shooting test.

When the instructor asked where she learned to shoot like that, she simply said, “My dad is a cop.”

“No further explanation required,” he said.

This was about the time Kris asked me when she could start dating.

“When you’re sixteen,” I said. “And when you turn twenty-eight, I might stop going with you.”

Being a homicide detective can make you paranoid about protecting your family. Some say that paranoia is unreasonable, but not in my case. I had seen too many young women murdered by ruthless killers—some of whom the women had known and trusted.

That is one reason I asked my daughter to bring her male friends over so I could check them out. I did a rotten thing to my daughter one time. Her date came in this giant honking Buick station wagon, and he was so little, I couldn’t see him behind the wheel when he pulled into our driveway.

I was home from work, but just for dinner, and I was still wearing my gun. I waited for him to walk up to the front door, and just as he was ringing the doorbell, I yanked the door open and said, “what do you want?”

I thought he had pissed his pants.

Kris didn’t speak to me for two weeks. What can I say? I enjoyed playing the evil father. I trained both her and my son in firearms and self-defense because of disturbing cases like the one in this chapter, which I took more personally than most because it involved the murders of innocent young women like the one we were raising at the time.

Getting emotionally involved in my police work took a toll on me, as it does on every man and woman in law enforcement, whether they acknowledge it or not.

Yet, my empathy for victims also allowed me to hang on to my humanity. I have no regrets. Well, maybe in my darkest hours, I have some regrets. But my anger toward the killers, and my determination to seek justice made me push myself and my team all the harder.

That was the case with Micki Filmore, whose life ended at the age of twenty-two. This country girl from rural North Carolina had joined the army straight out of high school. She did a three-year tour of duty and saw a lot of the world before her service ended in December 1985.

Sadly, I was called to her one-bedroom in Pikes Peak Apartments seven months later, on July 19, 1986. One of her neighbors, Army Specialist Tracy Spencer, called us to say he’d walked by her apartment window and seen Micki sprawled on the floor. She didn’t move when he knocked on the window.

Spencer and his wife had seen their neighbor having pizza the night before. They said she had seemed fine then, so this alarmed him. He went back to his apartment and told his wife, Lisa.

They returned, and Spencer helped his wife climb through an open window of the apartment to check on Micki. They found a disturbing scene. She was dead and sprawled naked after an apparent sexual assault.

Our homicide unit was called to the apartment shortly thereafter, and we found the scene no less disturbing. The victim was on the floor with her legs apart. We wondered whether the killer had positioned her this way for a purpose.

She also had bruising around her neck, suggesting that she’d been raped and strangled. Nothing in the apartment appeared to be disturbed, raising the distinct possibility that rape and murder, not burglary, had been the killer’s goal.

There was no sign of forced entry, which also raised questions. Micki Filmore may have left her door unlocked, which seemed unlikely for a woman who had traveled the world through her military service.

The killer may have entered through the same unlocked window that the Spencers had used. Or, more likely, Micki may have known her killer and trusted him enough to let him in.

There was something particularly twisted in this case, and as the father of a young daughter, I left the murder scene with my stomach in knots. My sense was that we were dealing with a deranged and calculating killer.

I feared that unless we found this person soon, he would strike again.

My fear was not misplaced.

a greater sense of urgency

I always carried a sense of urgency into murder investigations. A killer was on the loose, after all. But I didn’t always have the sense of dread that came with this one. Part of it, I’m sure, was paternal. My young daughter lived in this city, too. Yet that didn’t explain the nagging sense that t

his was someone who was not done killing.

He had selected his victim, stalked her, and struck swiftly and viciously. I had the definite impression that he was a compulsive killer, who would not be satiated and, in fact, was probably already searching for his next victim.

I called in all available officers and detectives to interview residents of the apartment complex, which had a large contingent of military and former-military personnel. Colorado Springs had more than forty thousand military personnel assigned to five military bases in our area. Most were good citizens, but when you have a large group of individuals who have worked in violent environments and have access to firearms, there will always be a percentage who cause problems in the community.

We always had a very good relationship with the military police, who handled crimes on their bases while we handled those within our jurisdictions. We often socialized, as well as worked together on cases that crossed jurisdictional lines. The military’s Criminal Investigations Division (CID) team wore civilian clothes and carried the title “agent” rather than military rankings.

In recent years, the two separate law enforcement agencies worked together to solve a cold case dating back to my years with the Colorado Springs Police Department. This was a 1987 case of mine, which was similar to the Filmore murder. An active-duty soldier stationed at Fort Carson, Darlene Krashoc, twenty, was raped and murdered. Our patrol officers found her behind a Korean restaurant in the city on March 17.

She was last seen alive between midnight and one a.m., a mile from the restaurant, at a nightclub called Shuffles, where she was drinking and dancing with other soldiers. She’d been beaten and strangled, and it appeared that her body had been moved to the restaurant parking lot after she was killed.

We worked the investigation with the support of the CID agents from Fort Carson. Together, we collected evidence and interviewed witnesses, but we could never nail down a suspect, I’m afraid.

Eventually, her murder investigation was assigned to a cold case unit. Over the years, they reviewed it, and as the science of DNA testing and analysis improved, they kept on top of it to see how it might be applied in the Krashoc case.

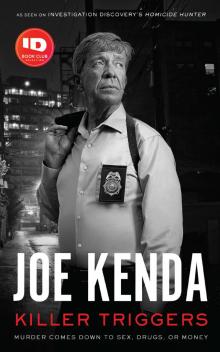

Killer Triggers

Killer Triggers