Killer Triggers Read online

Page 7

All these appeared to be in Hank Waller’s handwriting, which certainly cast him in a darker state of mind than the “compassionate” husband, father, and grandfather we’d heard about.

Most observers, in law enforcement or otherwise, might have homed in on the son-in-law, Bob Moore, as the likely suspect in this case. And certainly, I’ve worked many homicide investigations where the estranged husband or boyfriend did turn out to be the killer.

But that is why I always preach to my detectives and others I train that you cannot jump to conclusions on any case. You have to follow the evidence to wherever it leads you, without making assumptions.

The evidence in this homicide investigation kept leading us to the far more unlikely but undeniable conclusion that Henry “Hank” Waller, a respected former teacher, a part-time lawman, and an admired family man, had murdered three family members and then taken his own life.

Now, throughout this investigation, we certainly kept in mind that perhaps someone had set Waller up, using very elaborate measures. However, we did have an eyewitness neighbor who looked out her window and saw the complex manager arguing with his daughter in the parking lot just seconds before the fatal shot was fired.

That would be hard to fake. Not impossible, but very difficult.

On top of that, we had the “kill lists,” with handwriting that matched an unsent letter to Mary Elizabeth Waller, which talked about “a bad thing” that Bob Moore had done, and other family issues. It was signed, “Love, Dad.”

We talked to Mary Elizabeth about that letter and her father’s state of mind. She said that her mother had been telling her for months that there was something wrong with Hank. The sister in New Mexico also told us that her father had called her recently and seemed despondent over Linde’s separation from her husband.

“He was saying really, really irrational things like ‘I can’t allow this to happen.’ And ‘They’ll never stop me from seeing my grandson.’ ”

We also had multiple reports, from others who knew Waller well, that his mental state had become increasingly darker and more volatile since his stroke four years earlier. Waller had broken down while telling his pastor that he was depressed about his wife’s advancing multiple sclerosis, their financial challenges, and his daughter’s marital problems, especially if the breakup would mean less time with his grandson.

Another friend told us that Hank was so upset about Linde’s breakup that he was planning to take her out of his will and leave only his wife, Mary Elizabeth, and Brandon as his beneficiaries.

We did talk to a psychiatrist about Hank Waller’s stroke and the impact it might have had on his mental state. The shrink told us that strokes have been known to dramatically alter the personalities and behaviors of their victims.

I concluded that Mr. Waller felt he’d lost control of his family and his life and that he had decided to kill not only his wife, daughter, and grandchild, but also his son-in-law, Bob Moore. That is why he had invited him over for breakfast on the morning when all the killings occurred.

Who knows what might have happened if Moore hadn’t gone to work? He might well have died, too, or he might have prevented at least some of the deaths.

We surmised that Linde had declined to sit down to breakfast, and her father had confronted her as she went to her car. They argued briefly, and he shot her. Then he returned to the house and did the rest of the killings.

Including his innocent grandson—a true act of depravity, and perhaps one that Waller could not live with on his conscience, so he put the gun to his own head and pulled the trigger.

Sheer madness.

loss prevention

A week after we closed our investigation in this case, I received an invitation to speak to the Wallers’ grieving family and friends at Sunrise United Methodist Church, where Henry’s funeral was being held.

I was probably not the best choice to be anyone’s grief counselor—I struggled with my own job-induced demons—but as a public servant, I accepted the invitation out of duty. Given the tragic aspects of this case in which a man chose to murder his wife, daughter, and grandson, speaking publicly was not an easy thing for me to do, as you probably can understand.

I was also aware of the fact that grieving family members can have conflicted feelings about the homicide detectives who worked a case. Some are grateful. Others blame us or see us as uncaring.

So when I walked into this gathering of about thirty silent, staring people, I feared they thought of me as the bad guy in the room. Within seconds, however, a young woman approached me in tears and gave me a crushing hug.

“I’m Mary Elizabeth Waller,” she said. “I want to thank you so much for reaching out and telling me about this before I learned it from some other source. Ten minutes after you called, the news was on televisions all over the hospital.”

“Yes, I was afraid of that,” I told her. “I’m so sorry we couldn’t tell you in person.”

In speaking to her and the others, I did not try to make sense of these senseless acts.

“I just wish it were under better circumstances. What happened to the members of your congregation was a tragedy. The person you knew and loved is not the person who did this. A stroke unraveled the personality of Hank Waller, to the point of lunacy. I hope that in the future, other families will recognize the signs of mental illness and get professional help for the individual who is suffering.

“You don’t want to go through this sort of tragic and senseless loss.”

This was a fairly rare case back then—one in which an upstanding family man, a doting husband, father, and grandfather, turned into a murderous lunatic after suffering a series of strokes that altered his personality. But over the years, I handled many homicides in which the killer suffered from a mental illness of some sort.

The takeaway from this case, in my talk to those grieving friends and family, is that if someone you care about begins acting out of character—and especially if they seem to be depressed, paranoid, and withdrawn from their normal lives—please stage an intervention of some sort, for their safety and the safety of others. Tell them you want to take them to lunch or for ice cream, and then drive them to an appointment with a licensed therapist or counselor who can diagnose their problems and get them help.

The sad truth is that our country’s mental health systems have all but collapsed due to negligence and neglect by our government. There are very few safety nets remaining out there, and those that remain are severely frayed.

The one large public mental-health facility in the Colorado Springs area was seeing four thousand people a month the last time I checked. And those are just the people who understand that there is something wrong with them and they need help. Many people who could benefit from professional care end up on the streets and homeless because they can’t afford it, they can’t access it, or they don’t know how to find it.

Stephen King said, “Horror is the coming undone of something good,” and that can happen more easily than you might think.

Our mental health system has come undone, and horrors have resulted. And in this tragic case, Hank Waller, known to his friends as “the gentle giant,” was a good man who came undone and took his innocent loved ones with him.

my secret stalker

Just as an aside to this sad case, I once had a mentally deranged stalker who told a bunch of people that she wanted to kill “Kenda the cop.” I’d never had any contact with her, as far as I knew.

She had probably seen my name and photograph in the newspapers or on television. This was in the early 1990s, when we had a big run of homicides and I was always doing interviews.

This woman, who lived in an east-side apartment in Colorado Springs, was fine when she took her meds, but whenever she went off them, she got loopy and determined to take me out.

She was a tiny little thing, and none of her neighbors t

ook her seriously, so nobody bothered to warn me. Then she showed up at police headquarters one day, looking for yours truly and packing a semiautomatic Ruger Mini-14 assault rifle with a thirty-round magazine.

This was a serious weapon that could tear your ass in half. She had stolen it from a neighbor and came to the police department waving it around and screaming, “Kenda is a dead man!”

Some guys have groupies; I had a crazed would-be assassin.

Fortunately for my killer wannabe—and for me and other CSPD members—she had no idea how to chamber a round in that weapon, and our heroic officers on the front line at headquarters promptly disarmed her. They were well within their rights to shoot her on the spot, but she hadn’t yet aimed the rifle at anyone, which saved her skin. When they had her in cuffs, they asked her why she wanted to kill me.

“Everybody hates that cop Kenda,” she said.

I’m told one of my fellow officers replied, “Well, we hate him, too, but we haven’t tried to shoot him—yet.”

Chapter Four:

The Choirboy Gone Bad

the trigger: rage, revenge, and money

I have a friend who was a master of disaster. He spent years working in areas devastated by hurricanes, tornadoes, floods, and fires. He had to quit when the images began to haunt him.

He couldn’t walk or drive anywhere without picturing destruction. He’d go through a perfectly normal, nice neighborhood, and his mind would send images of it ripped apart. Bodies in trees and shrubs. Houses shredded or burned to the ground. Trees toppled. Power lines down. Gas and water lines ruptured.

I understood perfectly. It was the same for me and most veteran homicide detectives. Everywhere we go, we expect to encounter murder and mayhem, even in “normal” suburban neighborhoods with white picket fences and neatly trimmed yards.

As I used to tell new recruits at the police academy, violence can happen anywhere, and it can come from anyone. There is no one profile for a murderer. They come in all shapes and sizes, all colors, all religions, all ages, and all socioeconomic levels. We learn to prepare ourselves for the worst from every person, in every environment and in any situation.

It’s not that we are demented, pessimistic, or cursed souls. We simply live with the knowledge that cruelty and violence can happen anywhere, at any time, even in the most seemingly serene settings.

And so it was in this case.

The Limbricks were known as a hardworking, churchgoing family living the American dream. They had a nice two-story red-brick house, guarded by a giant maple tree, on Potter Street in a middle-class Colorado Springs neighborhood.

Charles was a long-distance trucker, which kept him on the road for weeks at a time. His wife, Betty Jean, drove a school bus and held other jobs while raising their three daughters to adulthood.

Their youngest child and only son, Chuck Jr., was still at home, attending junior high school. He was a good student and known as the best singer and musician in his school and his church. He’d been something of a musical prodigy. He began playing drums in his church band at the age of five. Three years later, he added the bass guitar to his repertoire.

Chuckie and his mother shared a musical bond. She loved to sing gospel music in the church choir. He loved to sing with her and even wrote songs about her. Chuckie would later recall of his mother, “Music brought her a lot of relief from, you know, the pain she probably was feeling in her life.”

After saying that, he declined to explain the origins or source of her pain. Some would claim later that there was marital turmoil in the outwardly peaceful Limbrick home. Some even raised questions about infidelity on both sides.

We considered that scenario as the possible trigger in this case, but in truth, we never quite figured out what set off the killer. This one was a cypher. A lot of people who saw the good in Chuckie were shocked when the bad appeared.

And his dark side showed up time after time until, finally, after he’d caused a lot of pain, suffering, and death, his time ran out.

middle-class murder

When forty-two-year-old Betty Jean Limbrick was murdered in September 1988 in her own home, neighbors expressed shock and grief. She seemed like an all-American mom with a lot to live for. But when we took the call and went to her home, the much-admired Betty Jean was facedown at the foot of the stairs in the lower hallway of their split-level home and very much dead.

Nearly all the blood in her body had drained out and pooled around her.

“She was so well respected,” a neighbor told me. “She didn’t have an enemy in the world.”

“Well, no,” I said. “She had one enemy: the person who shot her, not once but twice, and killed her.”

Betty Jean typically came home after the morning shift driving a District 11 school bus, took a little break, and returned to drive her load of kids home after school. She didn’t make the second shift this time.

Her son had found her, according to the patrol officers at the scene when I arrived.

“Where’s he?” I asked.

The officer pointed to Chuck Limbrick, and my first impression was not a good one. He was sitting on the front-porch steps, with his head against a column, sound asleep.

Chaos reigns all around him. Flashing lights, cops, reporters, and ambulance crews. And the kid who just found his mother shot to death in their home is sleeping peacefully on the porch?

That’s not cool. It’s cold.

“Wake his ass up, and put him in a squad car. I don’t want anybody talking to him until we are ready,” I said.

Then I noticed that one of our detectives had another kid in a squad car, talking intensely with him.

“Who’s that?” I asked the patrol officer.

“That’s the son’s buddy. He was with him when they found her.”

The kid looks like a dog shitting razor blades. He’s shaking and bawling and jabbering away. The detective with him looked out the window of the squad car, made eye contact with me, and gave a thumbs-up.

I liked that. The buddy was shaken up, and he was a talker.

crime scene

I found it helpful to inspect a crime scene before talking to any witnesses, victims, or suspects. I like to form my own impression of what went down before hearing their stories.

I walked in the house—neatly kept, not flashy, but nice enough. I walked down a short flight of stairs to the lower level, where Mrs. Limbrick’s body remained. The walls around her had blood spray on them, which is indicative of a high-velocity bullet wound. The gunshot produced a cloud of blood, a red mist, causing the spatter pattern.

The blood pool around the body was difficult to avoid as I bent down to make a preliminary check of her fatal wounds. I hated stepping in blood, for all sorts of reasons, but sometimes there was no other way to get to the victim.

I practically had to squat down in it to examine her head wound, a single-entry close-contact gunshot to the left temple. The gun had to be only inches from her head when fired. Now, that might have been an indication of a suicide, except that there was also a gunshot wound in her right hand and shoulder. The bullet entered at the joint of her middle finger and exited from her palm, then went through her shoulder.

The hand shot was likely the first. The second shot, fired directly into her head at close range, looked like something an assassin would administer.

This was not something you’d expect to see done to a hardworking, churchgoing mother of four in middle America. The weapon was a serious piece of firepower: a .357 Magnum.

reading the signs

This woman thought to lack enemies had suffered an extremely violent attack at the hands of someone who made sure she did not survive it. This looked like a personal vendetta killing to me, one in which the killer knew the victim and, for whatever reason, hated her.

Unlike so many of the homicides I’d handled, th

is one did not serve up an immediate list of likely suspects. The victim did not live in a high-crime area teeming with violent criminals and drug abusers. She did not stay out late at night in bars, nightclubs, or strip joints.

Had she come home and encountered an intruder, or a burglary in progress? That was one potential scenario. Another possibility, as mentioned earlier, was that Mrs. Limbrick did have an enemy, and not just someone who coveted her church pew or wanted her bus-driving job.

This enemy wanted her dead and gone from this world. Who could hate sweet-natured Betty Jean Limbrick that much?

Our investigation was already hindered by the fact that the killer had at least a two-hour head start on our investigation. You may have heard me mention this before, but I hate giving bad people a head start.

Call me competitive if you must, but I do not like being late to the starting line. That gives the killer too much time to toss the weapon into a river, drive a hundred miles from the murder scene, or dream up a decent alibi.

I would have been perfectly okay with setting up a hotline for local killers. They could have called me immediately after dispatching their victims, thus eliminating any lag time in my pursuit of them. Maybe that was hoping for too much, but a guy can dream, can’t he?

I’d finished my preliminary examination of the victim’s wounds when one of our officers asked me to come upstairs. Our search had turned up Mrs. Limbrick’s purse, which appeared to have been rifled. The zippered pockets of her wallet were all open, and while several credit cards were present, along with her driver’s license, there was no cash in her wallet.

For all I knew at that point, Mrs. Limbrick was a proud member of our cashless society, but the condition of her purse and contents suggested someone had gone through it in a hurry.

We came upon additional evidence supporting the possibility that the victim may have interrupted a burglary in progress. A couple of lamps were turned over and some furniture moved around. Even so, we didn’t find clothes thrown out of closets, or drawers dumped upside down, which is usually the case in residential burglaries.

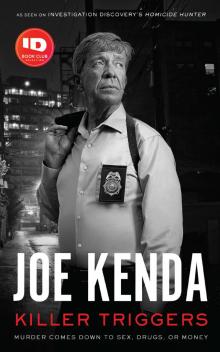

Killer Triggers

Killer Triggers